Post Category : Local Archaeology

“The Last Great Battle”

Battle of Belly River, 1870

For International Indigenous Day, there are an unlimited number of topics that we could discuss. This year, since Lethbridge is my home and I’m interested in it’s history, I decided to write about “The Battle of the Belly River”, also called the “The Last Great Indian Battle”. One of the city’s largest parks was named after this event, and is called “Indian Battle Park”. The name of the park has been debated in the recent years, however, it has yet to adopt a new name, but that is a topic for a different day.

The battle that we’re referring to occurred on October 25, 1870. To put this into perspective, the signing of Treaty 7 occurred in 1877 and Fort Whoop Up (the first version, known as Fort Hamilton) was built in 1869.

Significance

This battle was significant for a number of reasons. It is acknowledged that other battles were larger and of greater importance, but the Battle of 1870 was important for three reasons (Johnston 1997:21). Johnston stated that since:

“eye-witness accounts are available, the battle has become one of the best recorded of inter-tribal conflicts; it took place within and adjacent to what became a large city and has excited the imagination and interest of local citizens for nearly [now well over] one hundred years; and it was the last great inter-tribal battle to be fought in North America” (Johnston 1997:21).

The battle may have started at Fort Whoop-Up, or it may have started three miles from the Fort, or it may have begun closer to Raymond (Johnston 1997). But, by all accounts, the battle was scattered and spread out throughout the Oldman River valley. It was not an organized battle and there were multiple skirmish sites throughout the river valley.

The battle was between the Cree and Assiniboine against the Blackfoot. There are multiple accounts of the story, told by various individuals.

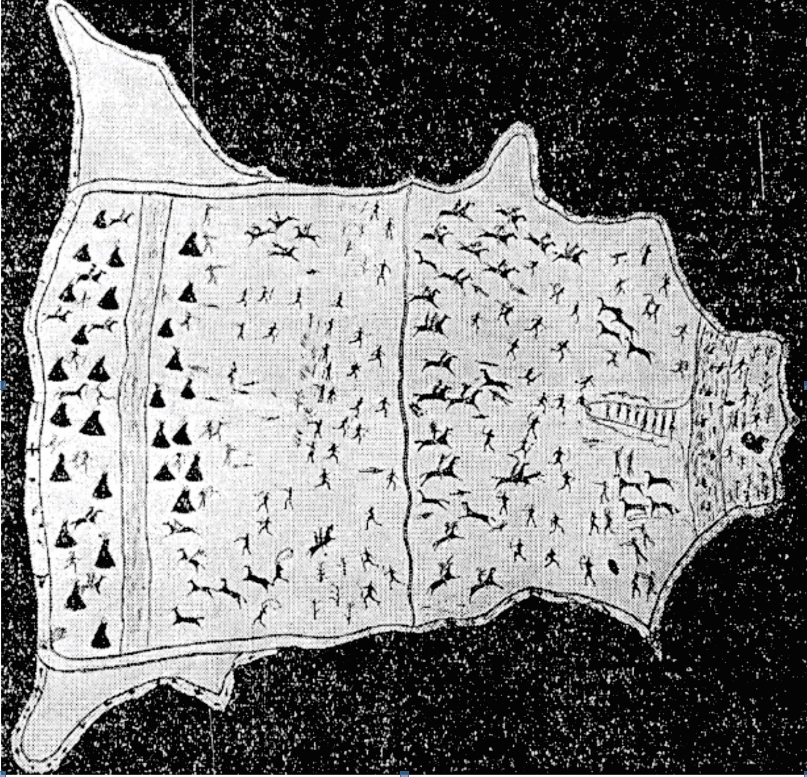

Big Battle Robe (Dempsey 2007:174)

Why did the battle start?

In 1869, smallpox reached the Blackfoot, and by spring of 1870 the disease had decimated the First Nations groups. According to Touchie (2009) the Blackfoot groups had lost over 2200 members and the Cree, Assiniboine, and Gros Ventres experienced similar losses. Thus, in the fall of 1870, the Cree attacked the Blackfoot when they thought the Blackfoot were weak and vulnerable and they believed that they would easily claim victory.

A powerful Blackfoot leader, Seen-From-Afar, died in 1869 during this epidemic. When he was alive, he avoided conflict with the Cree and maintained peace throughout 1866 until his death (Dempsey 2017). Seen-From-Afar was born around 1810 in southern Alberta and was the son of Two Suns (Dempsey 2017). He was a powerful leader of the Bloods (Blackfoot), and led approximately 2,500 people. It is said that after his death, his remains were transported to Lethbridge because he loved this place so much. His final resting place may be located in the vicinity of another of Lethbridges’ Parks, Pavan Park or the adjacent Alexander Wilderness Park/Peenaquim Park.

What happened?

According to one account, the Cree and Assiniboine warriors attacked a small, isolated Blackfoot camp where they killed a chief and stole the horses (Dempsey 2007:173). However, the noise of rifles firing and dogs howling alerted the rest of the Blackfoot camps, who then realized that they were under attack and nearby Blackfoot warriors joined the fight. Some of the Blackfoot women swam across the river to the main camp to get help, while other women defended themselves and their families with weapons such as tomahawks.

Many of the Blackfoot warriors were positioned on top of the coulee and fired downward at the Cree and Assiniboine warriors who were in the valley. The Blackfoot outnumbered the Cree and Assiniboine, and were using more advanced weapons (repeating rifles, needle guns, and revolvers). Therefore, the Cree were forced east into the Oldman River (Dempsey 2007:175).

The Cree and Assiniboine warriors only had old muskets, and bows and arrows (1890, cited in Johnston 1997:10). Hand to hand combat took place in the river valley once the Blackfoot descended into the valley. It’s said that the river turned red from the blood. However, once the Cree and Assiniboine started to retreat, the Blackfoot allowed them to escape.

View from the top of the coulee, looking northeast over the valley (author’s photo).

Casualties

It is estimated that there were about 600 to 800 Cree and Assiniboine warriors involved in the battle, and that the Blackfoot far outnumbered them (Johnston 1997:8).The number of casualties is not known. However, the Cree may have lost between 200-300 warriors while the Blackfoot lost about 40 men, and between 50-60 were wounded during the course of the battle.

Aftermath

After the battle, the Cree and the Blackfoot entered into an informal peace treaty in January of 1871, when the Cree sent the Blackfoot a gift of tobacco. A formal peace treaty was established the following autumn along the Red Deer River. There is a monument located in Wetaskiwin that commemorates the peace treaty made between the Blackfoot and the Cree Nations. I

t is said that the two chiefs, Buffalo Child of the Blackfoot and Little Bear of the Cree, inadvertently created peace by sharing a peace pipe. This treaty endures to this day, and the battle represents the beginning of an established peace.

Alyssa Hamza

Project Archaeologist