Post Category : Archaeonerdism Archaeotourism Local Archaeology

“If you move another step towards me, I’ll blow you to hell!” The story of Fort Whoop-Up and Whisky Trading Forts of Southern Alberta

In the 1860s, Southern Alberta was home to several American whisky trading posts that sold liquor and guns to the local Indigenous groups in exchange for bison robes. These transactions occurred despite the United States Law of 1832 that banned liquor sales to the Indigenous groups. One such fort was Fort Hamilton (Later renamed to Fort Whoop-Up), established by John Healy and Alfred Hamilton in 1869 on a traditional camping spot of the Kainai. Although they had a successful first year, the fort was burnt down by the Kainai when the traders were prepping to leave for the summer.

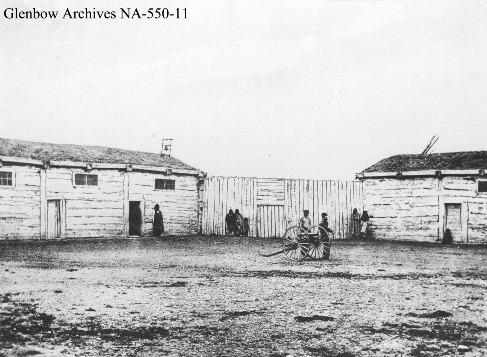

Figure 2: Members of the Kainai Nation outside Fort Whoop-Up (c) Wikimedia Commons

Healy and Hamilton built a second, more elaborate fort the following year in 1870. The fort was only active in the winter when furs were most valuable. The traders would be there for eight months and then head back to Fort Benton in Montana for four months. The local Indigenous groups would set up camps outside the fort, where they would gamble, race horses, and drink the (usually watered-down) liquor they acquired from the fort. These groups were the Kainai, Piegan, and Siksika. These Blackfoot speaking people referred to the fort as akaisakoyi or “many dead” in their language. This name refers to the many conflicts between the white men at the fort and the Natives, but also approximately 70 died from alcohol related deaths (poisoning, passing out in the snow, etc.)

These conflicts were predominantly between the American wolf-hunters (Wolfers) and the Blackfoot. Due to these conflicts, the fort was renowned as a dangerous place by travelers in the region. Reverend John McDougall recalled stopping near the fort to eat when “several men rode out and surrounded them. The men were drunk and had just come from fighting with the Natives. One was all shot up and looking for a doctor.”

The animosity between the two groups stemmed from the Wolfers practice of sprinkling poison on bison carcasses and return to collect wolf hides to sell at the fort. This was not seen as honorable by the Blackfoot, but it also had unintended consequences of killing people and their dogs if they did not know the Wolfers poisoned the carcass. Sometimes the Blackfoot would follow the Wolfers and steal the wolves before the Wolfers would return, often leading to violence.

Of particular concern to the other white traders in the Whoop-Up region was rumours certain forts were selling repeating rifles to the Blackfoot when only single shift muzzleloaders were allowed. A posse called the “Spitzee Calvary” of around 30-40 men were formed by John Evans and Harry “Kamoose” Taylor to travel to each fort and force the traders to sign an agreement at gunpoint and often took furs and supplies as a fine. When the approached John Healy, now running the nearby Fort Kipp, Healy welcomed them into the cramped trading room:

“guilty and you be damned. What right have you to come down here and try me. You’re a mad dog among a pack of decent hounds. They were good men until you (Evans and Taylor) got among them.” Healy pulled out a shotgun and leveled it at the men. “If you move a foot. If you move another step towards me I’ll blow you to hell!” In another version of the story, he held a lit cigar over an open powder keg. There are various accounts of this incident; some suggest it happened at Whoop-Up and others suggest it happened a Fort Kipp. I did some digging, and Healy clarifies that it happened at Fort Kipp in a 1903 issue of the journal Forest and Stream.

In response to the stories of violence, the illegal liquor sales, and rumours an American flag was being flown at Fort Whoop-Up, the North West Mounted Police were formed to clean out Whoop-Up. When they arrived in October 1874 after three months of hard travel on the plains, their leader, James MacLeod, set up his men expecting a battle but only found a man with a wooden leg, Dave Akers, and a few Blackfoot women. Exhausted from the long march and frustrated that Healy and Hamilton were nowhere to be found, the NWMP asked for whiskey, but Akers let them know they had none. MacLeod and his men thoroughly searched the entire fort, upstairs, downstairs, in every hole and crevice but could not find any whiskey.

After the NWMP cemented their presence in the region, illegal whisky trading declined, and an NWMP barracks was eventually established at Fort Whoop-Up. The NWMP presence continued until the barracks were burned down in 1888, and the NWMP ultimately abandoned in 1890.

A modern recreation of the fort can be visited in Lethbridge. Follow this link to learn more about Fort Whoop-Up and plan your visit.

Source:

Fooks, Georgia Green (1983). Fort Whoop-Up : Alberta’s First and Most Notorious Whiskey Fort. Whoop-up Country Chapter, Historical Society of Alberta.