Post Category : Archaeonerdism Local Archaeology

The 9 types of Medicine Wheels in Alberta

Figure 1: Aerial view of the Majorville Medicine Wheel (Courtesy of Alberta Environment and Parks)

Most people are familiar with Medicine Wheels, either from popular culture or books such as “Canada’s Stonehenge” by Gordon Freeman. Many people might not know that while they are found all over the Northern Plains in Montana, Wyoming, and Saskatchewan, they are most numerous in southern Alberta. There are currently 57 documented medicine wheels in Alberta.

For those unfamiliar with medicine wheels, they are configurations of stone with at least two of the following: a central cairn, one or more concentric stone rings, or two or more radiating lines from the central cairn. Frequently, there are several other stone features present at the site, including hearths, tipi rings, anthropomorphic figures, and secondary cairns.

The term “medicine wheel” was first used in an issue of Forest and Stream, referring to the Bighorn medicine wheel located near Medicine Mountain in Wyoming. Since then, the term has become a basic generic category. But within this basic category are nine subgroups, which are discussed in further detail below.

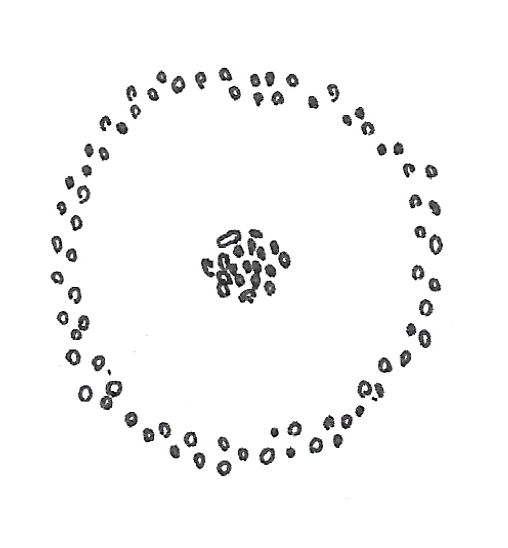

- Type: Subgroup 1

- Description: Central cairn surrounded by a stone circle.

- # in Alberta: 24

- Discussion: Typically found on high hills away from significant water bodies where high frequencies of glacial till are present (Brumley 1988). The presence of these types of medicine wheels on high peaks may result from the proximity to cobble and boulder-strewn moraine, which was used in the construction of the rock feature (Peck and Wetzel 2018). As for function, small artifacts and religious paraphernalia within cairns suggest ceremonial locations.

- Type: Subgroup 2

- Description: Central cairn surrounded by a stone circle but includes a “passageway.”

- # in Alberta: 5

- Discussion: These medicine wheels are similar to Subgroup 1 with the exception of the passageway. These types of Medicine Wheels are found on high hills and low terraces near waterbodies. Of the five medicine wheels observed in Alberta, there is no consistency in terms of the passageway’s orientation.

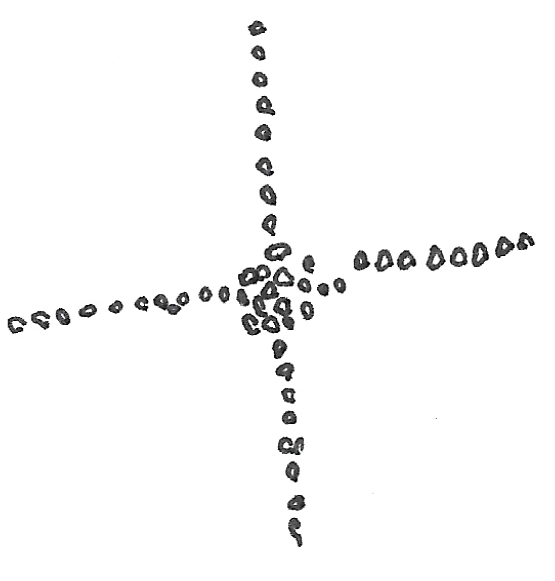

- Type: Subgroup 3

- Description: Central cairn with two or more radiating lines out from the centre.

- # in Alberta: 5

- Discussion: In 1880, John McLean observed the construction of a Subgroup 3 Medicine Wheel while at Fort McLeod and noted, “Several great battles were fought, and these cairns were placed to commemorate these events and probably where great warriors died” (McLean 1896: 579). This explanation is similar to the ethnographic descriptions for Subgroups 4 and 7 Medicine Wheels, and all may have served a similar function but vary stylistically.

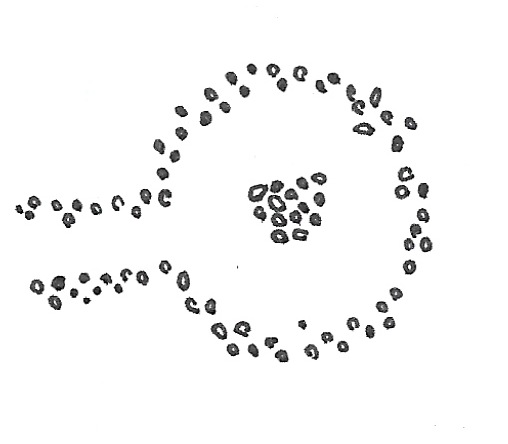

- Type: Subgroup 4

- Description: A stone ring that has two or more stone lines extending outward from its margins.

- # in Alberta: 16

- Discussion: In contrast to Subgroup 1, these are typically found on prairie surfaces along major river valleys or central portion of a river valley bottom or, in other words, typical camp locations (Peck and Wetzel 2018). Ethnographic evidence (Kehoe and Dempsey 1956) suggests these medicine wheels mark where a prominent Blackfoot leader died or was a favorite camp location of the leader. These types of medicine wheels’ location make sense when considering the areas they are found, although some are located on high hills back from waterbodies. What the radiating lines mean is debated, but all agree it is an indication of the Chief’s status that died. While one informant that spoke with Dempsey suggested the lines point to the direction of the warpath the Chief went to war, another informant suggested they are directions from which people would come to feast with the great leader (Kehoe and Dempsey 1956). Although both informants may be correct, and functions may have shifted over time.

- Type: Subgroup 5

- Description: A stone ring that is dissected into segments by four or more interior stone lines radiating outward from a central origin point.

- # in Alberta: 1

- Discussion: Archaeologists have only recorded one in Alberta (Jamieson’s Place Medicine Wheel, EePi-2). This subgroup is similar in style to the subgroup 6 Medicine Wheel. According to researchers at the site, it is possible there was a central cairn at the site but was destroyed due to vandalism (Thorpe 1982). If that is the case, it would be reclassified as a subgroup 6 Medicine Wheel.

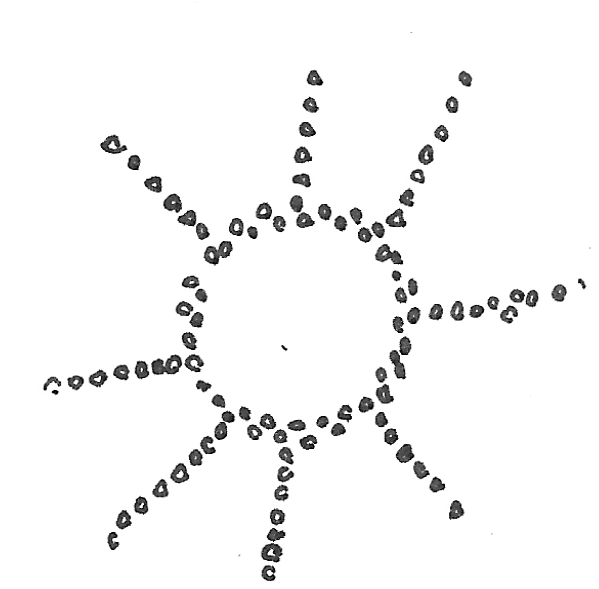

- Type: Subgroup 6

- Description: A central stone cairn surrounded by a stone ring, two or more interior stone lines that connect the stone ring to the cairn.

- # in Alberta: 1

- Discussion: The only Subgroup 6 Medicine Wheel recorded in Alberta is Alberta’s most famous Medicine Wheel, Majorville Carin and Medicine Wheel. Located on a high hill overlooking the Bow River valley, the wheel has 27 badly disturbed stone lines that extend from the central cairn. Archaeologists excavated the southern half of the cairn in 1977 (Calder) and discovered that the central cairn was constructed over 5000 years in accretional domes. Analysis of the 17,000+ artifacts recovered suggests the cultural practice originated from 3200-2500 BCE and continued to be used uniformly until around 1000 BC. Use of the cairn decline until about 200 AD when use picked up again until European contact. The artifacts recovered include ceremonial artifacts and utilitarian artifacts (tools, flakes, cores, etc.); however, these utilitarian artifacts may have been offerings for success in the hunt.

- Archaeastronomy: While some astronomical orientations are present at the site, there is not enough evidence to confirm if these alignments were intentional or merely an accidental coincidence. This evidence would have to come from oral or written sources or see consistency between the similar Medicine Wheels. Additionally, some astronomical alignments suggested at Majorville incorporate glacial till likely deposited naturally.

- Type: Subgroup 7

- Description: A central stone cairn surrounded by a stone ring, two or more interior stone lines that connect the stone ring to the cairn.

- # in Alberta: 3

- Discussion: These medicine wheels are similar in style and locations Subgroup 3 and 4 Medicine Wheels. One Subgroup 7 Medicine Wheel, Many Islands Medicine Wheel, was excavated in 1983. Over 2000 artifacts recovered but mostly represent campsite activities with an emphasis on a lithic workshop of Swan River Chert (Brumley 1988). A lithic workshop’s presence reinforces that the medicine wheel was likely constructed at the campsite location of the Blackfoot, where a leader died.

- Type: Subgroup 8

- Description: A central stone cairn and ring, two or more lines extend outward from the cairn and pass through the wall before terminating.

- # in Alberta: 0 (2 in Saskatchewan)

- Discussion: Could be a variation on Subgroups 3, 4, and 7 but limited information.

- Type: Subgroup 9

- Description: Two double circles with four or more spokes terminating just outside the outer ring.

- # in Alberta: 1

- Discussion: This is a recently added subgroup (Reeves and Kennedy 2018), based on a type first identified by Deaver (1987). This type of medicine wheel is found at the Grassy Bend Medicine Wheel (DgPc-6), located along the Milk River. The double circles may represent a smaller lodge erected within a a more extensive lodge for ceremonial purposes (Reeves and Kennedy 2018).