Post Category : Local Archaeology Method & Theory Special Finds

The One That Got Away

In this blog series, we will be reviewing and summarizing recent archaeological research occurring in the province and around the world. To see the original article, and others like it check out the Blue Book Series presented by the Archaeological Survey of Alberta.

When we find animal bone in an archaeological site, we can usually tell whether that animal died of natural causes, or if they were hunted and butchered by people. Evidence of butchery is sometimes obvious. We can see cut marks on the bone that are left behind when a sharp metal or stone knife cut into the outer layer of tissue that makes up bone. We can also see different fracture patterns in how the bone breaks. You can butcher an animal with an axe, leaving behind deep gouges in the bones, or using a saw which leaves distinct striations in the cuts.

Telling how an animal was hunted is more difficult. We often have to infer how the animal died based on the surrounding evidence. If we are looking a site like Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump, we can make a pretty good guess that the animals died from falling off the cliff. If we find a bison skeleton surrounded by stone arrowheads, it likely was shot using a bow. Very rarely do we ever see “the smoking gun” in archaeology. However, in the case of the Pibroch Vertebra we have a unique specimen that provides an insight into how people were hunting in the past. In an article published in the Archaeological Survey of Alberta Occasional Paper Series, Dr. Jack Ives at the University of Alberta and Bob Dawe at the Royal Alberta Museum reviewed their findings from the Pibroch Vertebra.

The Pibroch bison vertebra has graced the halls of the Royal Alberta Museum for almost 30 years. It was found in the summer of 1987 by Bill Vaughn, roughly four miles west of the town of Pibroch, Alberta. When Mr. Vaughn picked up the vertebra, he noticed a very unusual growth on the left side with what looked like a stone projectile point inside. Mr. Vaughn donated his oddity to the Royal Alberta Museum, where a CT-scan revealed that a large stone point had indeed been embedded into the side of the vertebrae, and that the injury had completely healed over. When bone tissue is injured, the cells will grow over the site of the injury in an attempt to repair the damage. In the case of this bison, the stone point never came out and the bone healed around the point. This process is known as ossification. Researchers estimated that that the callus around the injury would have taken years to grow its current size.

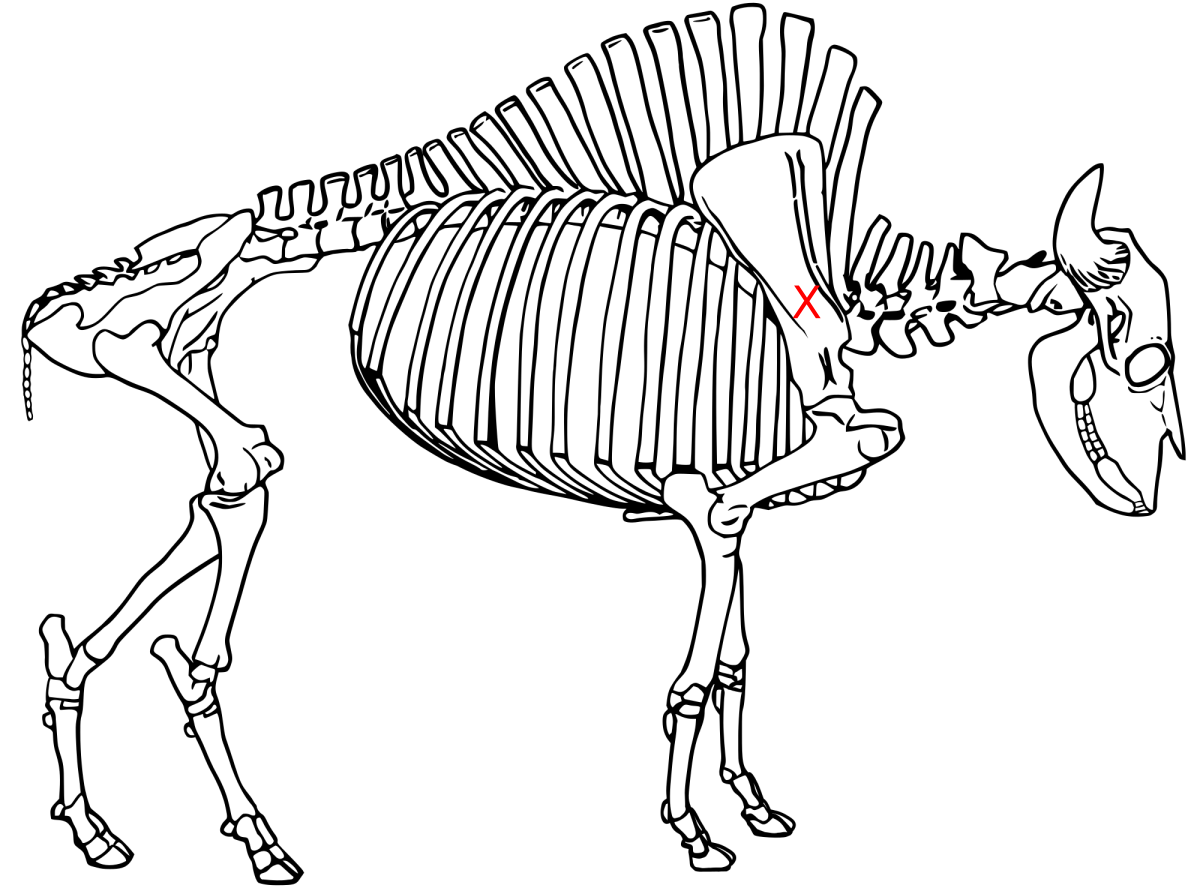

Because of the size of the stone point, Ives and his colleagues suspected that the specimen might date back to the Early Precontact Period in Alberta. Only the blade of the point has survived, so it is hard to say for certain what archaeological phase it belonged to, but it was clear from the breadth of the projectile that it had originally been hafted to either a spear or an atlatl dart. These hunting technologies are thought to be more common in older time periods. A piece of the vertebra was sent for radiocarbon dating, and the result came back showing that the animal died 1,700 years ago, much more recent than originally suspected. This radiocarbon date places the Pibroch Vertebra into the Besant Phase in Alberta, a period between 2000 to 1000 years ago. It is during this time that we see the start of intensive communal bison hunting activities like bison jumps and pounds occurring on the Northern Plains. However, the atlatl remains the dominant hunting weapon over the bow and arrow.

Based on where the stone point had hit the animal, Ives and his colleagues suggest that the hunter had been aiming for the kill zone of the bison. The Pibroch vertebra is one of the seven cervical vertebrae that make up the neck, which places it directly above the heart and lungs of the animal. The hunter’s dart likely flew higher than intended, and hit just above the shoulder of the animal. It is not clear whether the Pibroch bison was injured during a communal bison kill like Head-Smashed-In or whether it represents an episode of an individual stalking prey. We do know that 1700 years ago a hunter missed their shot, and went home hungry.

If you would like to learn more about this article, you can find it, and many other excellent articles like it in the Blue Book Series. Images of the Pibroch Vertebra were provided by the Royal Alberta Museum and the CT Scan Imagery was provided by the Cross Cancer Institute.